Hello! I haven’t had much writing time this week, so this is an extract from a bigger thing I’m doing. It’s very relevant to readers of this newsletter, though — so I hope you like it, and maybe get something out of it. Please let me know! - JS

In 1986, a series of comics was released that changed the way most people looked at the medium forever.

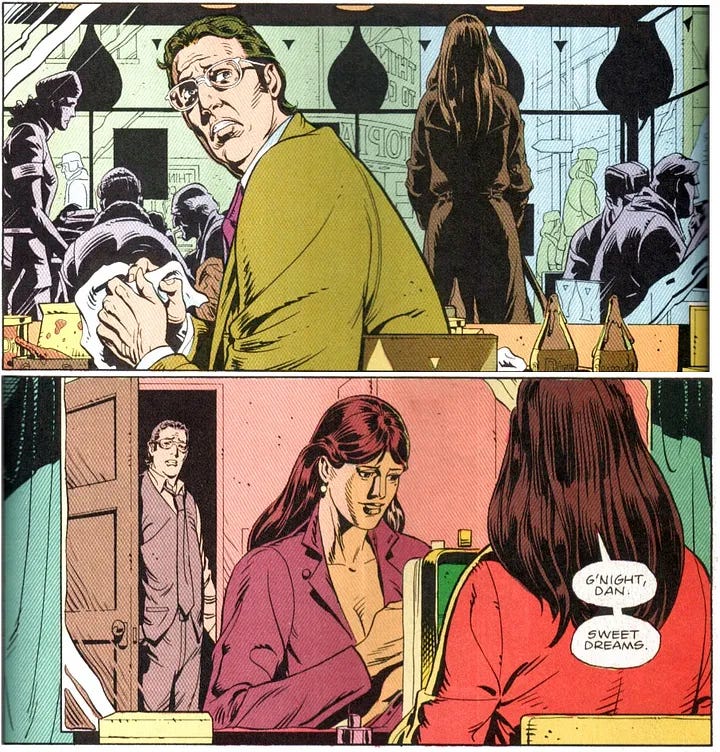

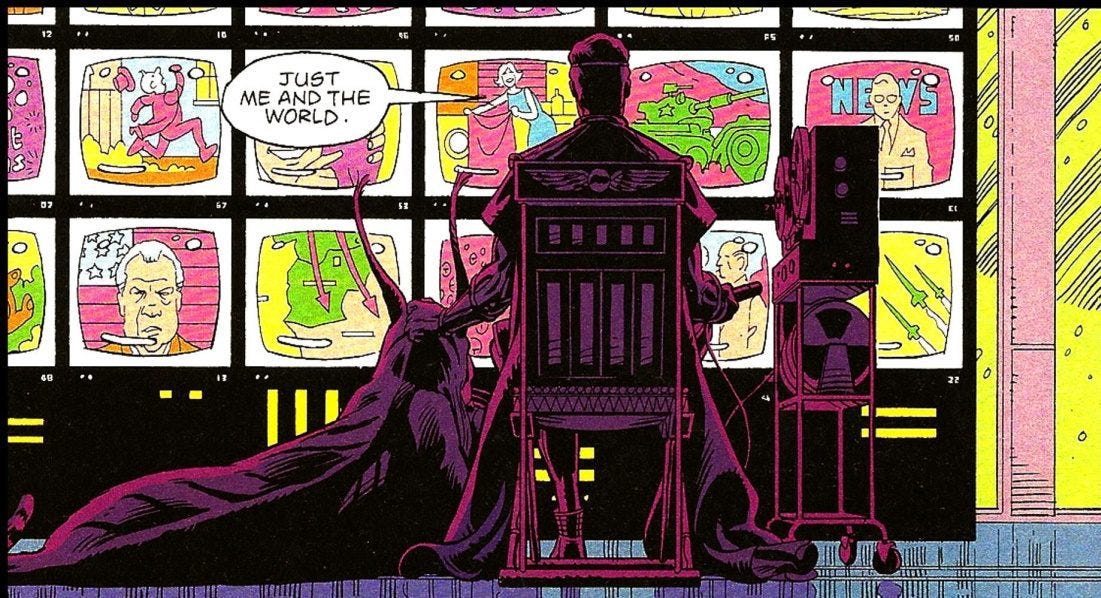

These days, it’s common to see comics that deconstruct the tropes of the superhero genre, layering complex plotlines together and giving their superpowered characters all-too-human frailties and flaws. But when Alan Moore’s Watchmen released, it was like nothing most readers had ever experienced — in the words of Time critic Lev Grossman, “a watershed in the evolution of a young medium.”

What Moore and artist Dave Gibbons created is a piece of art with that plays with the limitations and possibilities of the comic format itself. Issue number six, "The Abyss Gazes Also," begins with a brightly-coloured palette that descends into darker shades as it explores anti-hero Rorschach’s descent into his past, finally ending on a single completely black panel. Issue five, "Fearful Symmetry," is almost perfectly symmetrical itself, starting at the issue’s shocking centrepiece and expanding outwards into pairs of pages that reflect one another in colour, composition, and themes.

First released as a 12-issue limited series, Watchmen won a Hugo Award — widely considered the premier prize in science fiction — the year after its release, and went on to be voted one of Time magazine’s best 100 novels by critics in a 2010 poll.

Obviously, it wasn’t Moore’s first attempt at writing a comic.

Although he was already well known for his work on series like Swamp Thing, V For Vendetta and Miracleman when he pitched Watchmen to DC, the series came almost a decade into a career that started with Moore writing for local newspaper the Northants Post. One of his first regular gigs was Maxwell The Magic Cat, a five-panel strip published under a pseudonym so that he could keep claiming unemployment benefits. By 1980, he was writing for Doctor Who Magazine — but struggled when pitching ideas to iconic British comic 2000AD, having suggestions for a Judge Dredd strip turned down by editor Alan Grant.

Eventually, Grant suggested that Moore try his hand at writing Future Shocks, self-contained short stories with a darkly funny feel that worked as a sort of testing ground for new artists and writers.

Future shocks were usually only five or six pages long, but for Moore, those few pages felt expansive: after telling stories in just a few panels on Maxwell The Magic Cat, and then in a couple of pages each in Doctor Who, Future Shocks were the perfect place to start stuffing more in. Moore revelled in the freedom, creating entire worlds and then (sometimes literally) destroying them in just a handful of pages each.

It was also another perfect playground for testing out ideas that would later reappear later. In Watchmen, the only character with superpowers is Dr Manhattan, a physicist who develops the ability to observe and manipulate matter at a sub-atomic level following a lab accident. Alongside his other powers, the doc sees time from a non-linear perspective — sometimes experiencing several moments at once, or carrying on conversations in multiple timelines. This was mind-bending stuff for many readers — but maybe not for fans of Maxwell The Magic Cat. Maxwell, something of a godlike presence himself, frequently talks to readers and questions the constraints of the comic he’s appearing in. In one strip, the fourth-wall-breaking feline chats to himself across multiple panels, asking his alter-ego in panel five to give him the punchline for the week’s strip while the Maxwell from panel two waves across the space-comic continuum at him.

In one of Moore’s Future Shocks, the idea of non-linear time reappears, as the crew of a spaceship are gradually all infected with the ‘alien idea’ that “If all time is simultaneous and all events happen in a single instant, then time is but a figment of mind…”

In another story, The Regrettable Ruse of Rocket Redglare, Moore introduces an ageing, overweight superhero, coming out of retirement to deal with his nemesis one more time — a decade before Watchmen’s Nite Owl did the same thing. There’s even a character called Rorschach in another Shock, though he’s a normal murderer rather than a masked vigilante.

Soon enough, Moore would have much more space to play with. When the big American publishers took an interest, he took all the knowledge about storytelling and deconstructing old tropes he’d acquired and then he went on to create some of the most iconic comics of the 20th century — and he wasn’t the only British writer to do it. Future Shocks was a proving ground for a generation of artists and writers who went on to reshape the American landscape — Grant Morrison, who went on to write some of the most popular Batman and Superman stories ever published, started out there, as did Mark Millar, whose later comics Kick-Ass, Wanted, and Kingsman, became successful film franchises.

Why did so many of these sort-of-household names get their start penning six-page stories about supervillain academies and intergalactic cleaning crews? Well, partly because that was what was available to them: as they entered the industry, 2000AD was one of the biggest and most prestigious comics to write for in the UK, and the editors didn’t let untested writers jump straight into writing Judge Dredd. But was there something about writing these shorts that prepared them to succeed in the hyper-competitive international comics market? A reason why these writers found fame and film deals when their American contemporaries often didn’t?

Well, maybe.

In his book Art & Fear, photographer David Bayles tells the story of a ceramics teacher who announces on the first day of a new class that he’ll be dividing the students into two groups: all those on the left side of the studio will graded solely on the quantity of work they produce, all those on the right solely on quality. He’s not even looking for a specific number of pots from the ‘quantity’ group — he’s just going to weigh them on a set of bathroom scales, and give an A to anyone who produces 50 pounds of pots. The other group, meanwhile, only need to produce a single pot: but it has to be perfect to earn that same A grade.

Even if you haven’t heard this story before, you’ve probably guessed the outcome by now — the quantity group made the best pots, getting their mistakes out of the way early and learning from every clunky, misshapen not-quite-pot, while those looking for perfection never just got down to it and did the work. But maybe it seems a little too perfect as a parable to be real — the sort of story you make up to back up a point you’re already planning to make? Well, as it turns out, the story is sort-of true: it’s based on a friend of the author’s who ran a photography class and did just the same thing: offering one half of his class an A grade for simply turning in 100 photographs at the end of the semester, while just expecting a single picture from the other half. Real life, of courses, mirrored Bayles’ story — the photographers who took dozens of shots improved over time, while the rest spent their time worrying about perfection and never quite getting there.

This approach — creating a lot of distinct pieces of work, but also doing it on a strict deadline — is exactly what Future Shocks demanded of its artists and writers. “I really, really wanted a regular strip.” Moore says of his time on the series, in an interview with comics journalist Bill Baker. “But I didn’t get that. I was being offered short four or five-page stories where everything had to be done in those five pages. And, looking back, it was the best possible education that I could have had in how to construct a story.”

In a short story, Moore explains, you have to do everything you do in a longer one — introducing characters, setting up the world they inhabit, and giving them compelling reasons to interact — but you have to do it faster. You learn to start with a bang, keep the narrative going, and then come to a satisfying conclusion, in the space of just a few pages. And when you’ve got more space to play with — 24 pages, say, or a 12-issue series — you can just scale up, giving depth to the characters and developing subplots but still knowing the essentials of how everything fits together.

But there’s more, and it might explain why the photography anecdote is actually better than the pottery one to explain how creative improvement often works. In 2006, Dartmouth business professor Alva Taylor and Professor of Entrepreneurship Henrich Greve collaborated on a paper titled “Superman or the Fantastic Four? Knowledge Combination and Experience in Innovative Teams”, in which they analysed the output of over 200 comic creators to see what factors made their work successful. They expected that experience and resources would play a significant role — that the creators who’d been working for longest, or had the support of the bigger companies — would succeed. They were wrong — what made the biggest difference was how many of twenty-two genres ranging from crime and comedy to fantasy and sci-fi each creator had worked in. Creators who’d worked across a range of genres were more successful on average, more likely to innovate, and more likely produce a smash hit.

It’s possible something similar happened with a whole generation of British comics writers. Look at the 30 Future Shocks Moore produced, and you’ll see that he covered about a dozen of the genres from the Dartmouth study in less than three years, sometimes combining them in weird or wonderful ways. Even before he started working on 2000AD, he was experimenting with different voices and formats, trying his hand at comedic detective stories one month and poetry-laced sci-fi the next. In the process, he also tried countless styles of storytelling — sometimes cramming every space on the page with speech bubbles and visual puns, sometimes barely using dialogue at all. And so when he came to bigger projects like V For Vendetta — where artist David Lloyd convinced him to ditch the typical comic page furniture — he already had the experience to make it work.

Moore certainly made conscious efforts to improve his own output — when he was first pitching to 2000AD, he asked fellow writer Steve Moore to critique his work, rewriting whole comics after his friend covered them in red pen. “He was saying things like ‘This panel description is unclear. You’ve given the artist two moments to choose from in this one picture. Tidy that up. This balloon is too long.” he says. But for writers with deadlines, the process of improvement isn’t always focused: it’s a struggle just to turn out a strip every week, let alone think about making it better.

Short stories don’t feel fashionable: you don’t get to see your book cover in shops if you write one, there’s basically zero chance of you writing a breakthrough smash that makes you a millionaire, and the indulgence of a whole short story collection is something that only well-established writers and dabbling film stars get. Writing one short story will not change your life, and neither will writing three or four, or (probably) a dozen. But short stories are a condensed education in writing longer stories: like Moore’s early comics, each one requires well-defined characters and a plot arc, an attention-grabbing opening and a satisfying ending.

A novel is intimidating: even typing enough words to write one is difficult, and you don’t want to unleash it on the world until it’s right, which is why so many end up half-finished. But a short story is easy — you can write one in an afternoon. And short stories let you practice the same skills as novels, except you can do it over a much more condensed timeline, then open yourself up to feedback without so much of your own heart on the line. Does your story have a clear plot arc and a satisfying ending? Do you grab the reader’s interest with the first page, the first paragraph, the first line? Is the dialogue believable? Have you stripped out the well-worn similes and metaphors, and replaced them with fresh turns of phrase that give your work its own style? It’s incredibly unlikely that you’ll do every one of these things the first time you sit down to write a book, but if you’re dashing out one story after another, you can fix one thing each time, until your twelfth story is far better than your first. One day, maybe you’ll write something that everyone’s still talking about almost 40 years after you make it. And even if you don’t, you’ll have a bunch of tales to tell.

Have a great weekend!

Joel x

Stuff I like

📝 Article - David Mamet’s memo to “The Unit” writing staff

You’ll have to forgive this being in ALL CAPS, it makes it almost unreadable — but there’s a bunch of good stuff in here, memorably delivered, on making every scene dramatic.

🎙️Podcast - Simon Miller on positivity in wrestling

Simon Miller was a contemporary of mine back when I worked on games magazines, and we even worked together - for about three weeks! - when I worked on Men’s Fitness magazine. Eventually, he went to do the one thing he’s always wanted to do — being a wrestler — and the success he’s made of it is down at least in part to the relentless positivity and enthusiasm he brings to everything he does. Even if you don’t know your Randy Ortons from your Randy Savages, this is well worth a listen.

🎥 Video - Gladiator | Turning Spectacle into a Meaningful Story

My fave Tom Van Der Linden does it again, with the best thinkpiece I’ve read/heard/seen on Gladiator as the new film comes out. Briefly, the point is that unlike in many films, where the story stops for spectacle, Gladiator makes spectacle the point — and that’s why it’s so memorable. It’s also the perfect re-intro to Gladiator if you don’t want to rewatch it before the sequel. Are you not entertained?

🧐 Quote of the week

“Dry your eyes. For you are life, rarer than a quark and unpredictable beyond the dreams of Heisenberg; the clay in which the forces that shape all things leave their fingerprints most clearly. Dry your eyes, and let’s go home.”

From Watchmen, by Alan Moore

Like this newsletter?

Please forward it to someone else! Also, if you’ve got a book or an article you think I should read, or something you think I should watch or try, please send it my way.

And if you haven’t already, please check out my YouTube channel, where I deep-dive into stuff like productivity, lifelong learning, piano and Brazilian jiu-jitsu.

This is great